A couple of years ago, I wrote about absolute versus relative returns. Given the latest market run, I am getting a lot of questions about chasing returns, and individuals comparing themselves to the S&P 500 index. Historically, trying to beat a benchmark index leads to poor outcomes. However, understanding absolute and relative returns can help solve this issue. Notably, while most investors say they want relative returns, they want absolute returns. The problem, as we discussed in “Benchmarking Has More Risk Than You Think,” is that investors are often unaware of how much risk they are taking. To wit:

“There are many reasons why you shouldn’t chase an index over time and why you see statistics such as ‘80% of all funds underperform the S&P 500’ in any given year. The impact of share buybacks, substitutions, lack of taxes, no trading costs, and replacement all contribute to the index’s outperformance over those investing real dollars who do not receive the same advantages. More importantly, any portfolio allocated differently than the benchmark to provide for lower volatility, income, or long-term financial planning and capital preservation will also underperform the index. Therefore, comparing your portfolio to the S&P 500 is inherently ‘apples to oranges’ and will always lead to disappointing outcomes.“

But here is the only question that matters in the relative versus absolute returns debate:

“What’s more important – matching an index during a bull cycle, or protecting capital during a bear cycle?”

You can’t have both.

I have had many discussions with clients, prospects, and listeners about “absolute returns” in portfolio management versus “relative returns.” The most common response to the debate generally begins with:

“I understood the part up to where you started speaking.”

Kidding aside, the importance of the concept of absolute returns should not be dismissed. This is particularly true since Wall Street has trained most investors to believe that relative performance is all that matters.

Relative performance is the comparison of your portfolio’s returns to those of some benchmark index.

Absolute performance is the return of the portfolio itself on a year-over-year basis.

Wall Street wants you to focus on “relative returns” because Wall Street needs you to continually “comparison shop.”

Why Wall Street Wants You To Compare

If comparing absolute vs. relative returns, consider the following: “Comparison is the root cause of more unhappiness in the world than anything else.”

Perhaps it is inevitable that human beings, given that we are social animals, have an urge to compare ourselves with one another. Such is particularly the case since the rise of social media, where we are constantly bombarded by images of how well “everyone” else seems to be doing. Here is an example.

Assume your boss gave you a new Mercedes as a yearly bonus. You would be thrilled until you learned everyone in the office got two. Now you are upset because on a “relative” basis, you got less than everyone else. However, are you deprived on an absolute basis by getting a Mercedes?

Comparison-created unhappiness and insecurity are pervasive. Social media is full of images of people showing off their lavish lifestyles, giving you something to compare to. As noted, it is unsurprising that social media users are terminally unhappy.

The flaw of human nature is that whatever we have is enough, until we see someone else who has more.

Comparison in financial markets can lead to awful decisions, so investors have trouble being patient and letting whatever process they have work for them.

For example, you should be pleased if you made 12% on your investments but only needed 6%. However, you feel disappointed when you find out everyone else made 14%. But why? Does it make any difference?

Here is an ugly truth. Comparison-related unhappiness is for Wall Street’s benefit.

The financial services industry is predicated on upsetting people so they will move money around in a frenzy. Money in motion creates fees and commissions. Creating more benchmarks, products, and style boxes is nothing more than creating more things to compare with. The end result is that investors remain in a perpetual state of outrage.

Goal-Based Investing

Here’s an essential perspective on absolute vs. relative returns. Changing your view from “relative performance” to an “absolute” investment strategy can significantly increase your long-term results. This is because behavioral biases are controlled, leading to fewer emotionally driven investment decisions.

The first thing we do with every client is establish their investing goals. Often, investors have no idea what their money is supposed to be doing for them. Mostly, they think that if they buy stocks, those investments will ultimately increase and make them wealthy. However, without clear goals, investors tend to take on excessive risk, as investment decisions become based on emotions rather than a strategy.

The most significant contributor to long-term problems is comparing one’s portfolio to an all-equity index. This is hugely flawed, as there are many differences between an index and your portfolio.

The index contains no cash.

Indices have no life expectancy requirements, but you do.

An Index does not have to compensate for distributions to meet living requirements.

To match, much less beat, an index, you must take on an equivalent, or more, risk than the index.

Indexes have no taxes, costs, or other expenses associated with them.

An index can substitute at no penalty; you can’t.

Here is the point.

If you want to be happy, you first must eliminate what makes you unhappy, which is all of the comparisons.

Graphical Representation

Clients who have learned the wisdom of “enough” are significantly happier. Their benchmark is not an artificial one, but one based on their own goals and risk tolerance. They are comfortable that the risk they accept is within the range they can emotionally withstand. Crucially, they understand the game plan for getting from Point A (where they are now) to Point B (retirement, or wherever they want to get to). With that understanding, investing becomes a process to obtain their goals with as little risk as possible.

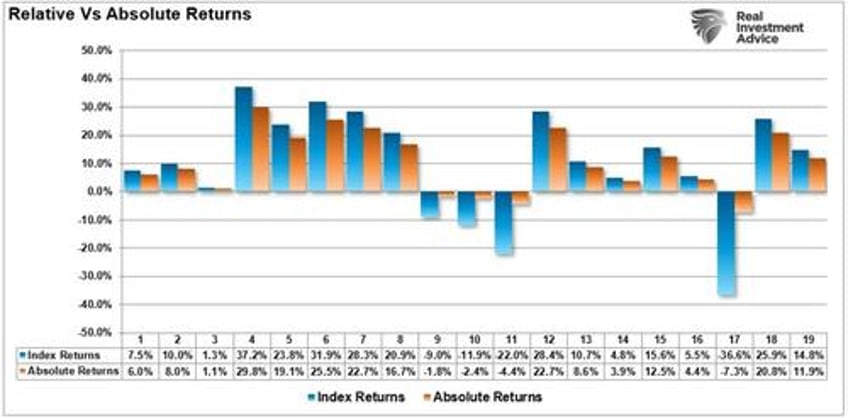

Let’s look at an example of what we are talking about. In the chart below, we look at some historical returns for the S&P 500 to predict what the next 20 years might look like. As you can see, there are quite a few up years and some down years.

What is essential for you to look at here is what the “Absolute Return” matrix looks like. We purposely made sure that in every up year the absolute return matrix underperformed the index, but in down years the absolute return model outperformed by not losing as much as the index. Were there down years in an absolute return portfolio – you bet! (More on the 80/20 rule of investing)

Slightly Better Than Average – Wins

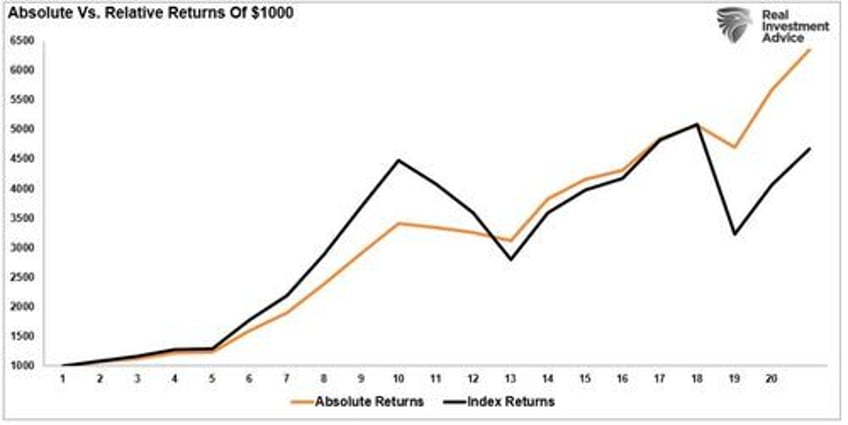

Look at the return matrix chart above. Assume that we invested $1000 in the Random Index Return Matrix and $1000 in the Absolute Return Matrix.

After the first year, most of you would be told that you need to move your money to another manager because he underperformed the index. The same is true in year two. However, in year three, you are feeling pretty good, but in every up year, you lag, so you chase another fund that beats the pants off the index the year before.

Here is another problem with relative return performance. In good years, you are happy because you are beating some index. However, when that index declines by 20%, and you are down 19%, Wall Street says you should be happy because you still beat the index.

I haven’t personally met anyone who was happy with that, have you? Just remember how you felt in March and April of this year during the “Liberation Day” sell-off.

The 7th Deadly Sin

The lesson we want to drive home here is the danger of following Wall Street’s advice of beating some arbitrary index from one year to the next. Most investors are taught to measure portfolio performance over a twelve-month period. However, that is absolutely the worst thing you can do. It is the same as going on a diet and weighing yourself every day. (Read “Solving The Anchoring Problem” for a better solution.)

If you could see the whole future in front of you, as in the chart above, it is very easy to make an investment decision knowing your eventual outcome. However, we don’t have that luxury. Instead, Wall Street suggests that if your fund manager lags in one year, you should move your money elsewhere. This forces you to chase performance, creating fees and commissions for Wall Street, not better outcomes for you.

We chase performance because we all suffer from the 7th deadly sin – Greed.

The problem with greed is that we can garner all the rewards without regard for the consequences. Instead, we should learn to “love what is enough.”

Absolute return investing can beat average market returns with less risk and volatility over time. Why? You can utilize the power of compounding returns by not losing your principal investment in down years. The problem with market benchmarking, and what financial advisors won’t tell you, is that you compound losses when there are back-to-back losing years. When contemplating absolute vs. relative returns, consider that.

Conclusion

If you want to win at the long-term investing game, Financial Resource Corporation sums it up best;

“For those who are not satisfied with simply beating the average over any given period, consider this: if an investor can consistently achieve slightly better than average returns each year over a 10-15 year period, then cumulatively over the full period they are likely to do better than roughly 80% or more of their peers. They may never have discovered a fund that ranked #1 over a subsequent one or three-year period. That ‘failure,’ however, is more than offset by their having avoided options that dramatically underperformed. Avoiding short-term under-performance is the key to long-term out-performance.

For those that are looking to find a new method of discerning the top ten funds for 2002, this study will prove frustrating. There are no magic short-cut solutions, and we urge our readers to abandon the illusive and ultimately counterproductive search for them. For those who are willing to restrain their short-term passions, embrace the virtue of being only slightly better than average, and wait for the benefits of this approach to compound into something much better…”

If you want to be a better investor, do what most investors don’t:

Look for stable returns, not the highest returns

Invest for a reasonable annual return to help you reach your investment goal.

Don’t compare yourself to some anomalous index.

Save, Save, Save!

Manage your money – after all, it is your money.

It’s not as hard as you think.