From his home in the far north of Ethiopia, Hagos can see Eritrean soldiers positioned on the other side of his town, Alitena, and says all his neighbours fear a full occupation.

“The Eritrean army can raid us anytime they choose,” said Hagos, resident of the tiny town of around 3,000 people.

Like other locals interviewed for this story, he asked that his name be changed for fear of reprisals.

Hagos regularly talks to people on the other side of town who already live “under occupation” by Eritrean forces.

They endure “sexual violence, abductions, forced labour, lootings, curfews, threats of harsh mandatory military service and other abuses,” he said.

“There is nobody lending an ear to my people’s plight,” he added. “The world is preoccupied with other crises.”

Ethiopia and Eritrea have been fighting over the remote and arid mountains of this region ever since Eritrea gained independence in 1993.

The area is populated by the Irob, a small ethnic group of a few tens of thousands.

When an Ethiopian civil war exploded in 2020 in the surrounding Tigray region, Eritrea supported Ethiopia’s federal forces against local rebels. The Irob were caught in the middle.

The neighbouring countries’ brief alliance came to an end with the peace deal that ended the war in 2022.

It called for the withdrawal of foreign — meaning Eritrean — forces. But having been excluded from the talks, Eritrea refused and has kept troops in several Ethiopian districts, according to the United Nations, as well as multiple foreign embassies and NGOs.

Asked by AFP, Eritrea’s Information Minister Yemane Ghebremeskel said he was “really sick and tired of these false allegations gullibly recycled by some news agencies”.

Its army units are only “stationed inside sovereign and internationally recognised Eritrean territories”, he said.

‘Abuse and misery’

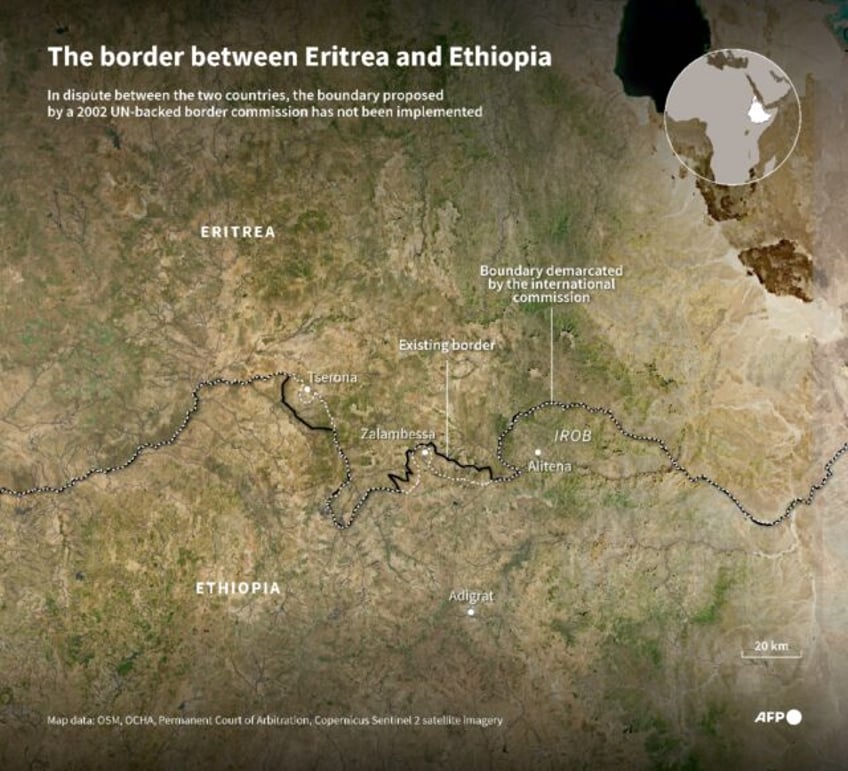

The border between Ethiopia and Eritrea, roughly 1,000 kilometres (640 miles) long, was the subject of a grinding war in 1998-2000 that left some 80,000 dead.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won a Nobel Peace Prize after coming to power in 2018 for his efforts at rapprochement, including the surprise decision to accept the findings of a UN-backed border commission that would hand several Ethiopian towns to Eritrea and split the Irob community in two.

But despite Abiy’s early endorsement, it has still not been implemented.

The commission-approved border would cut straight through Alitena. Eritrea’s forces have made it an effective reality without waiting for permission.

“My people, especially the youth, are unable to withstand the continued abuse and misery,” said one resident, who gave his name as Amanuel.

“They try to migrate to Europe through Libya or the Middle East through Yemen, often ending up dead in the deserts or in the Red Sea and Mediterranean,” he added.

At a hospital in the Ethiopian city of Adigrat, the second largest in the Tigrayan region, a nurse said she regularly treats women raped by Eritrean soldiers in the occupied areas.

“New cases of sexual violence are still coming to our medical facility, on average 15 to 20 cases daily including victims of gang rapes by three or more Eritrean soldiers,” she told AFP by telephone.

In recent months, there are fears of another war as Eritrea accuses Ethiopia, a landlocked country of some 130 million people, of eyeing its port at Assab.

“We’ve already been decimated,” Hagos said.

“If another conflict breaks out, the Irob will be wiped out.”