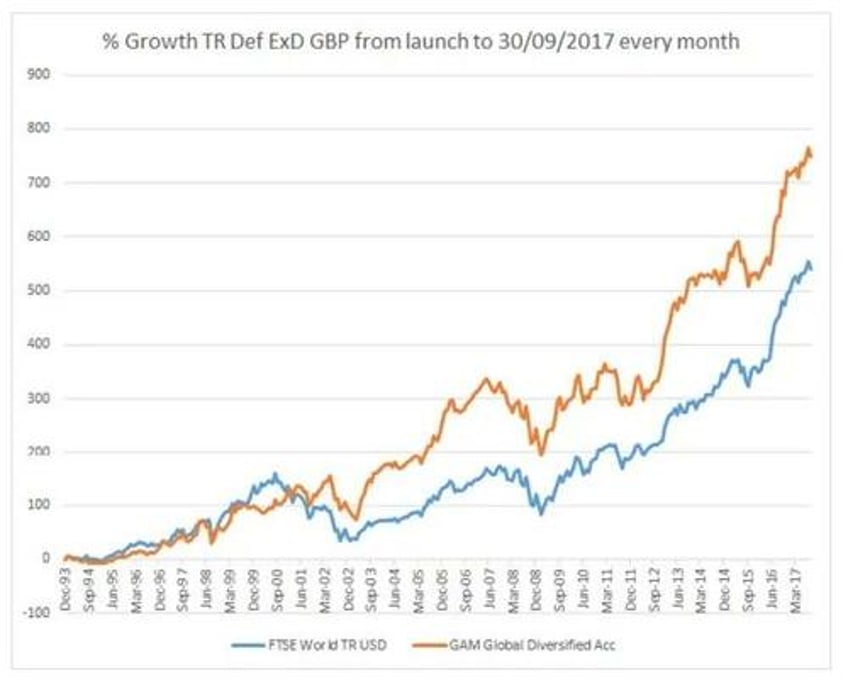

A well spent youth travelling around the world in my early 20s meant that I was very old to join UBS as a graduate trainee at the age of 25. I was even older to start as a fund management research analyst at the age of 27. I was extremely hungry for success, and I would spend all my time studying what the successful fund managers at my firm were doing. At the time the most successful manager at my firm as a chap called Andrew Green. He came to work maybe two or three days a week, and when asked about his investment ideas or philosophy, his answers were positively cryptic. He was the first, and probably truly most successful “contrarian” investor I have ever seen. Below chart is taken from an article announcing his retirement.

What you should notice is that he really began to outperform during the dot com bust, after underperforming during the dot com boom. Assets under management collapsed during the dot com boom, but as soon as the bubble burst, his style took off. He never really spoke to me (why would you speak to young analyst working for a different team), but I got on well with his analyst, and I asked him how did Andrew found his investment ideas? He told me looked for assets that were basing out of long bear market in either relative or nominal basis, and would take a small position, and then ramp it up as they began to outperform. It was this line of thinking that led him to be long gold miner DeepRoot Durban in 2000.

It was also this type of thinking that led him to be long Thailand, and particularly Thai banks in 2000. These were very deep contrarian ideas at the time.

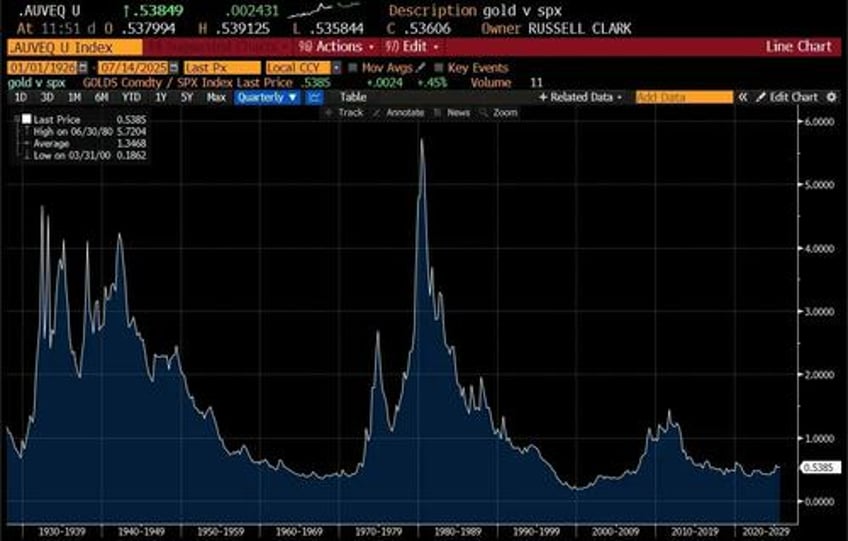

For me, I started to think about capital flows and asset markets (the title of this substack). Did the capital flows out of the US due to the bursting of the dot com bubble drive gold and Thai outperformance? Or was the improving outlook for Asia and commodities cause capital to be attracted to these assets? Or was the Truth somewhere in between? I never really got a definitive answer, but I do pay a lot respect to inflections are extreme points. It is why I put so much emphasis in the potential inflection of gold versus the S&P 500, which would be similar to an inflection 1929, 1970 and 2000.

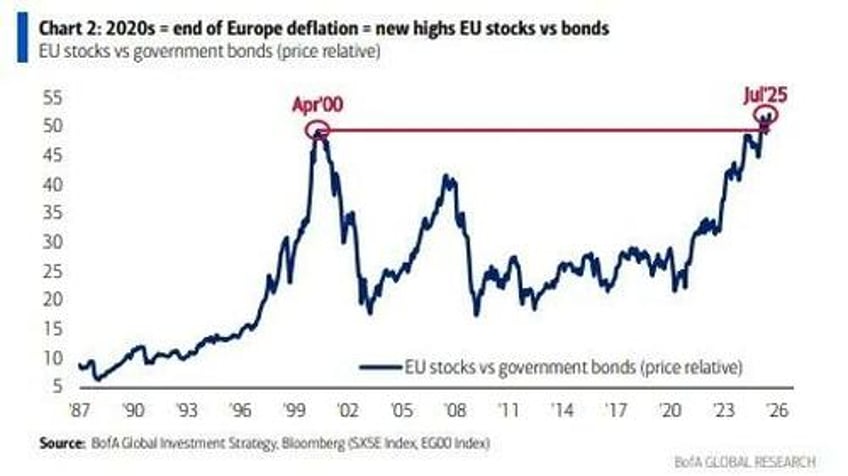

Getting away from gold, it is hard not see inflection points everywhere. Michael Hartnett from BoA has shown that we have suddenly reached a new high in European equities versus bonds.

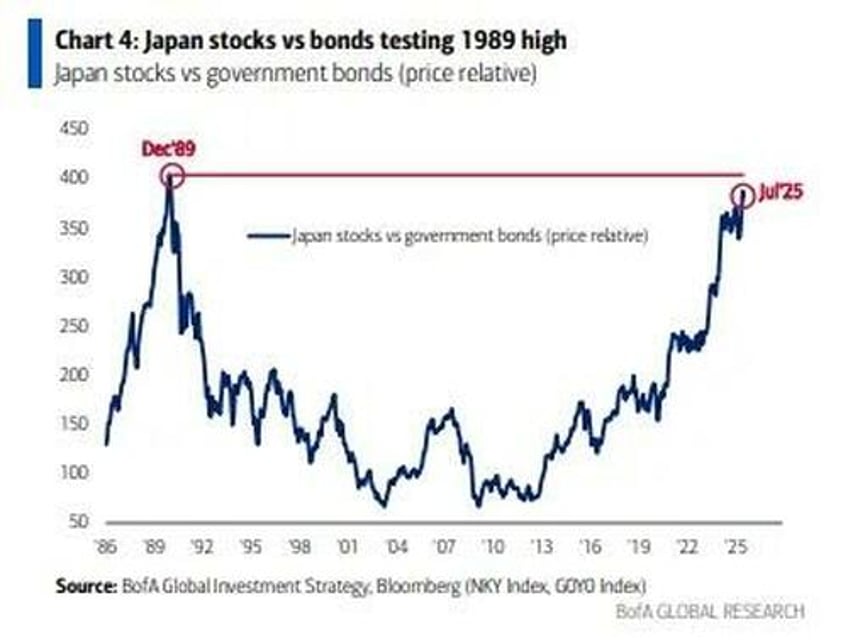

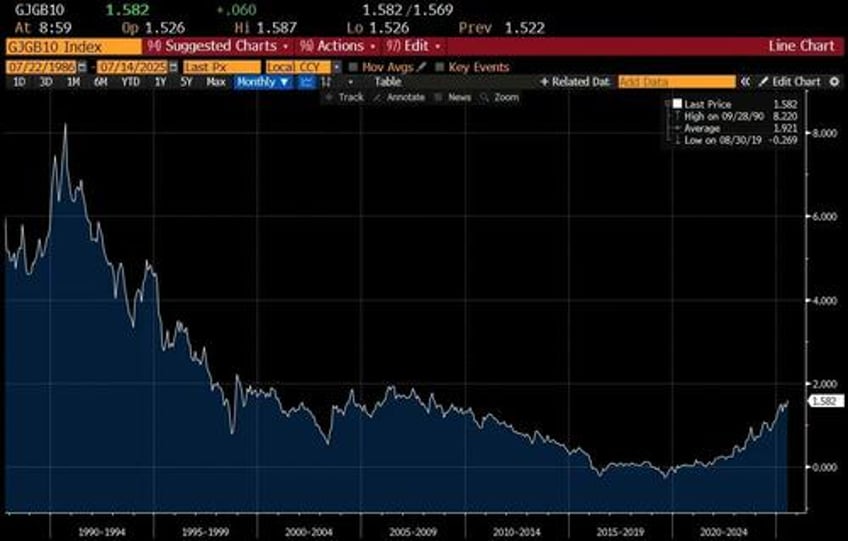

To go along with a similar move in Japan. From 1989 to 2013, you made more money in JGBs than you did in Japanese equities. 24 years of basically the complete opposite of modern money management theory.

This may seem to imply that it is time to get long bonds and short equity - as Andrew Green used to do, but that type of thinking would have made you bearish in 2016, 2020, and this year on US equities.

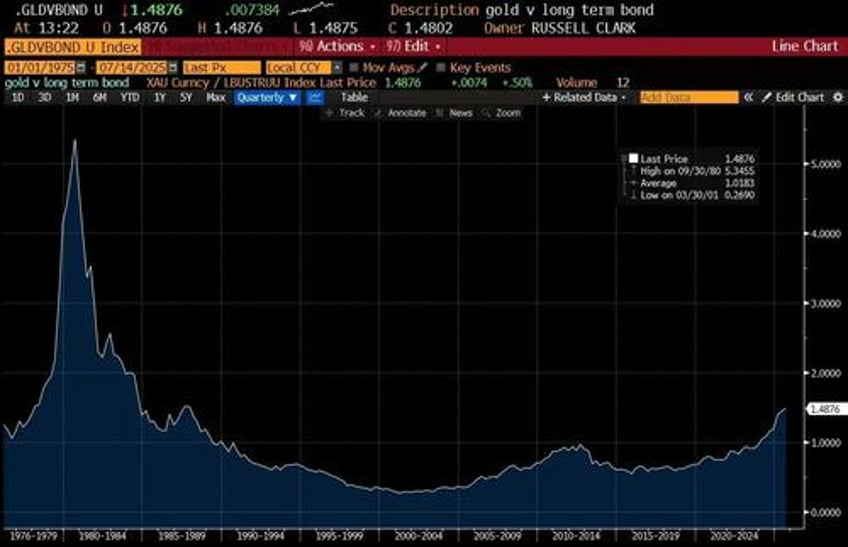

But it is hard to not get the feeling that equities have become extremely expensive versus bonds. The problem here is that I still rather like the look of gold versus US bonds. Or in other words, I don’t really like bonds here either.

And this is inline with a new cycle high in 10 year JGBS.

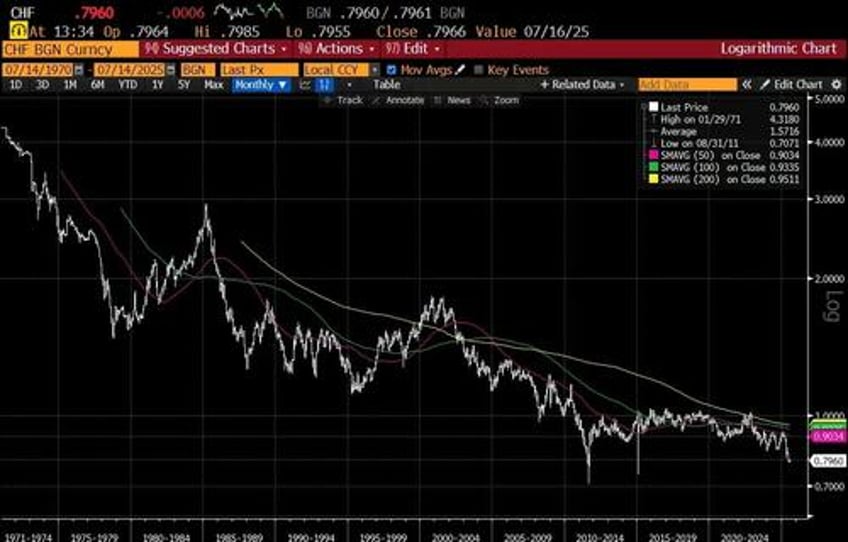

The most obvious story here is that makes sense to me is that government finances are in a mess - but the public will not accept any austerity. So at some point taxes on corporates and wealth or tariffs become the only option. And this creates a steady flow out of equities into gold, as we shift from wealth creation to wealth preservation. This seems inline with the Swiss Franc closing in on all time highs versus the US dollar. This graph is log scale.

That makes sense to me - but the question is what level of bond yield causes this political change? At what point do governments bow to the inevitable and move back from regressive taxation to progressive taxation? I find it odd to be a contrarian when record asset prices and record government deficits seem to scream out for some sort of progressive tax regime. I think this is what gold and Swiss Franc are telling you. Time will tell.