Colleges and universities across the country, both public and private, face financial challenges ahead of the upcoming academic year, regardless of their size, wealth, and prestige.

Layoffs or hiring and wage freezes were recently announced at affluent schools including Cornell, Temple, Northwestern, Duke, Notre Dame, Emory, the University systems in California, Maryland and Nebraska, and the University of Kansas, according to their respective websites.

Tuition hikes, meanwhile, are planned at public universities this fall in Alabama, Illinois, Minnesota, Montana, Oklahoma, and Oregon, in addition to several private schools, including Brigham Young, Stanford, Marquette, Georgetown, and most of the Ivy League institutions, their leaders announced in recent weeks.

Pennsylvania university system trustees announced May 22 that seven campuses will close within two years, and five more are still in scope to eventually shut down if enrollment doesn’t increase. Ten of the campuses reviewed had maintained courses with fewer than seven students, and nine campuses had fewer than 660 students. Collectively, the dozen campuses tallied a $29 million operating deficit in 2024.

With fewer prospective students due to the post-Great Recession birth dearth, fading public confidence in higher education, and federal funding cuts to colleges and universities, more schools in the years ahead will be forced to eliminate programs, raise prices, merge with other institutions, or close entirely unless they drastically change the way they do business, policy experts say.

“They’ll need to make these hard decisions,” Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars and a former tenured university professor and college provost, told The Epoch Times. “The real story is these institutions die hard. They don’t believe they are going to be subject to the laws of nature.”

Not Enough Students to Go Around

U.S. higher education enrollment, which sat at around 20 million, decreased by more than 1 million students between 2012 and 2022, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. A surprise spike in enrollments was reported for the 2022–23 school year, but that was mainly due to an increase in online enrollment and college-level course offerings at high schools.

The “enrollment cliff” has become a common phrase in higher education. The U.S. birth rate had already been declining steadily since 1990, and the Great Recession, which spanned from late 2007 to mid-2009, further exacerbated that trend. The number of babies born annually in this nation decreased from 4.2 million in 2008 to 3.6 million in 2020, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a 2023 research report from the Trellis Company, a nonprofit research firm.

Moreover, the Trellis report said, the college-going population is expected to decrease by 15 percent between 2025 and 2029.

Even though listed tuition prices at most schools have only increased at or below the rate of inflation since 2018, operating expenses and employee health insurance costs have skyrocketed. The average private college or university cuts its sticker price in half to maintain enrollment numbers even if they are running in the red, according to a December 2024 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. The report summarizes data from the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

In addition, the report said, 62 percent of students are enrolling in college the semester after their high school graduation, an 8 percent drop over the past decade, and an indication of “growing skepticism among the public about the value of higher education.”

There are already too many schools competing for a shrinking number of students. Between the 2022–23 and 2023–24 school years, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that 99 higher education institutions closed.

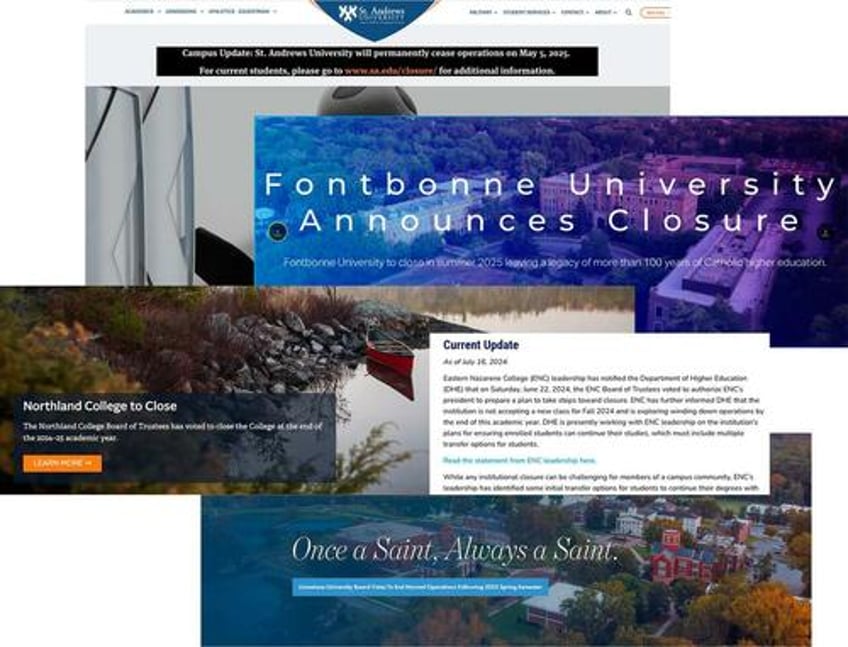

The list of 2025 closures includes St. Andrews University in North Carolina, Limestone University in South Carolina, Eastern Nazarene College in Massachusetts, Fontbonne University in Missouri, Northland College in Wisconsin, and Paier College in Connecticut.

There are still about 2 million unfilled slots across more than 5,000 U.S. colleges and universities, “not even close to equilibrium,” Gary Stocker, principal at data analytics company College Viability, previously told The Epoch Times.

Career, Cultural, and Technological Changes

The revived national interest in career and technical education also detracts from four-year college programs. A glance at community colleges and vocational training institutes across the nation indicates abundant certificate programs and “stackable credentials” toward college degrees where students can obtain workforce credentials in the health care, manufacturing, technology, agriculture, and hospitality industries in 15 weeks or less.

Wood, of the National Association of Scholars, said despite shrinking enrollment and low career prospects, too many institutions refuse to cut majors that have no return on investment.

Many programs, he added, originated as classical humanities such as English literature or history but evolved into ideological training sessions for subjects including “queer and transgender studies” or “colonialism” while administrative staffing to push and police those cultural shifts has ballooned in recent years, often with federal funding.

Under President Donald Trump’s executive orders prohibiting anti-Semitism, DEI, and transgender ideology, federal grants to several elite universities have been cut or frozen, and the 15 percent cap on indirect costs—such as administrative support, laboratory maintenance, and utilities—for research projects funded by the National Institutes of Health is intended to eliminate administrative bloat, Wood said.

Universities that the federal government deems have misused grants now face tuition hikes and/or cuts to maintain programs if a share of federal funding is cut, Wood said. Several of them have billions in their endowments, but those funds are often earmarked for specific scholarships, faculty chairs, or facility improvements and can’t be used to maintain administrator positions or discount tuition at the wholesale level.

Less prestigious schools that have small endowments are more likely to save money by putting off facility maintenance, even though they would be better off in the long term by cutting some academic programs and staff, Wood said.

The cost of student services at most residential schools is also rapidly increasing as schools emphasize the need for more counseling services and expensive interventions, Wood added.

Read the rest here...